The hedge fund disruption

Hedge funds went mainstream like a bankruptcy – very slowly and then all at once.

The combination of growing macroeconomic pressure on pensions and the success of a charismatic early hedge fund adopter would help drive trillions of dollars into hedge funds at the start of the century. The transition would disrupt traditional institutional investing, redraw the map of acceptable investment strategies, and create an asset class with $3.2 trillion under management in 2017.

But today, they’re hardly the disruptive force they once were. Instead, they’re an ordinary part of a portfolio that is under increasing pressure to cut fees and justify its position among other investments.

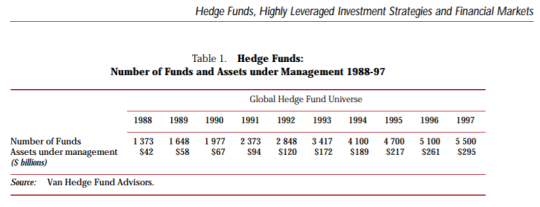

Hedge funds were a tiny category up until the late nineties. There were around fifty-five-hundred hedge funds managing a total of more than $295 billion in 1997 according to an OECD report, citing data from Van Hedge Fund Advisors. Each fund averaged just under $54m in assets under management. The number of funds that had reached the more than $100 million in AUM, let alone $1b in AUM, was miniscule.

Many of the leading managers would routinely post outsized returns. George Soros’ Quantum Fund “broke the bank of England” in 1992 when, having bet most all of the fund against the pound, he watched as prevailing economic circumstances forced the bank to devalue the pound. Former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad would go on to accuse George Soros of currency manipulation for similar outsize bets against and trading of the Ringgit during the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997. Meanwhile, Julian Robertson, who had started with $8m in 1980 had amassed $10.5b in 1997 and doubled to $22b in 1998.

Up until the mid-nineties, however, hedge funds had always existed in a kind of regulatory void, so they grew up in the confines of the portfolios of wealthy individuals. Many institutions wouldn’t consider them. But the success of a charismatic early hedge fund adopter would become a lodestar to institutional investors struggling with growing macroeconomic pressure. His example would set the stage for massive allocations to hedge funds.

David Swensen had begun to attract attention for his unorthodox approach to institutional investing. Swensen managed the Yale endowment, and under his guidance, it had set the pace for endowment performance. From 1985 to the year 2000, it grew ten-fold, from $1b to $10b. In the fiscal year 2000, alone, the endowment grew 41% to $10.1b and became the second largest endowment, next to Harvard. Swenson capped off this performance by publishing Pioneering Portfolio Management in the year 2000. The book would set the stage for a broad reconsideration of institutional investment strategies.

David Swensen’s exceptional returns shone a spotlight on the use of so-called alternative investments. His approach would reduce Yale’s market exposure through shifting the endowments investments toward alternatives: private equity, real assets and hedge funds. He argued that these so-called alternative investments were instrumental in “pushing back the efficient frontier.” The efficient frontier refers to Harry Markowitz’ statistical depiction of the trade-off between risk and return. Generally, the higher the return, the higher the risk. A good investment manager would only take as much risk as was warranted by the expected return - nothing more. But Swensen’s example suggested that including alternative assets would provide portfolios “higher returns for a given level of risk or with lower risk for a given level of return.” By embracing alternatives, Swensen argues, a manager could achieve higher possible returns without raising the level of risk.

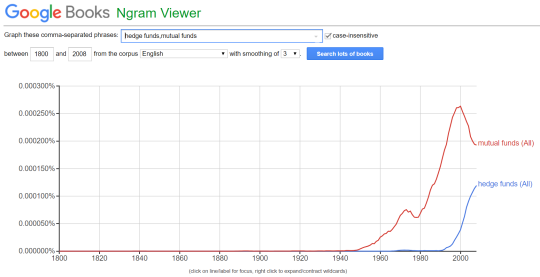

Swensen wasn’t the only one talking about alternatives. Google Books Ngram Viewer provides the relative incidence rate of terms throughout Google’s collection of digitized books. The incidence rate of mentions of the bigram “Hedge Funds” spikes dramatically from the late nineties through 2008. The incidence rate of mentions of the bigram “Mutual Funds,” however, declines from the year 2000. The conversation in published books clearly begins to coalesce around alternatives, such as hedge funds.

Meanwhile, the macroeconomic picture had turned against many institutional investors. Pension funds, in particular, were struggling. They had historically maintained a bond-heavy portfolio, and the bond-oriented portfolio had provided sufficient returns to match the liabilities of their participants. The average rate for a ten-year US Treasury bond, however, peaked at 15% in 1981, and from the 1980s onward, interest rates would enter a long-term, secular down-trend. The ability of pension funds to generate sufficient returns to cover their participants would steadily decline over the years. During the recession in the early 1990’s, the Federal Funds Rate declined to 3%, which drove down interest rates for other sovereign, municipal, corporate, as well as consumer borrowing. Pension funds would either have to raise the level of contributions from their participants or take on more risk to generate increased returns.

No one wants to pay more into their pension funds, so pension funds started to carry more risk. They allocated more capital to equities through the 1990s and the strategy did quite well. The strong bull market in the 1990s more than compensated for the declining returns of the bond market. In fact, some argued that the strong performance warranted an increase in pension benefits. In 1999, California lawmakers reviewed the state’s pension system for government employees, known as CalPERS, and proposed increasing benefits on the strength of strong investment returns. CalPERS considered the proposal and projected that over the next eleven years, the increase in benefits would require no additional funding from the state and, by extension, tax payers. CalPERS was not alone. Other state pension funds followed suit.

New Jersey, under the leadership of Christine Todd Whitman, made two bold moves in an effort to lower taxes for the state. First, Whitman began by withholding state contributions to the pension system in 1995. Whitman used the so-called “savings” to balance the state budget. The net impact on pension contributions by the state put “the employer contributions to the pension system this year [1995] will be as much as 96 percent below the amounts contributed in the early 1990's”. The decline in employer contributions reflected a reduction of “nearly $1 billion a year.” Ominously, Richard C. Leone, a former New Jersey State Treasurer and then president of the Twentieth Century Fund remarked, “There is no question but that this is creating future debt. This is just another way of getting around the balanced-budget requirement, a kind of deficit spending. It is the sort of thing that comes back to haunt you.”

Whitman then took the highly unusual step of using leverage to invest in equities. New Jersey sold $2.75 billion of bonds paying 7.6% interest in 1997. The proceeds went directly into an investment program in the state pension fund named the Pension Security Plan. Whitman claimed returns from the program would save taxpayers $45 billion and, in so doing, would help finance the tax cuts her Republican administration wanted to pass.

The Pension Security Plan worked handsomely, at first. The first full year of investment returns at the NJ Division of Investment had an average rate of return on the pension assets of 22.7 percent, so the returns more than compensated for the cost of capital. Research written at the time by the Pension Research Council at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in the volume Pensions in the Public Sector attributed staggering performance to the fund’s increasing exposure to equities: “The State Investment Council and Division of Investments has generated remarkable returns on pension asset investment, since it began to invest more of the pension assets in equities.“ The Pension Security Plan, in part, owed its success to a levered bet on the equity markets.

The expansion of benefits in California and the experiment in New Jersey both collided with a simple reality: markets go up and markets go down. The backslapping performance of the late-nineties turned quickly in the year 2000. From March, 2000, the Nasdaq would lose more than 70% of its value through the end of 2002. The S&P 500 would lose more than 35% of its value. California would have to increase its contribution to the pension system by a total of $18b over the next eleven years, from its 1999 projections. The so-called Pension Security Plan introduced by Christine Todd Whitman would ultimately not even cover the cost of capital, let alone finance the tax cuts. It earned less than 6% annually through 2009. The increased equity market exposure proved to be their undoing.

Pension funds, however, still needed returns. Bond yields only got worse when Federal Reserve Bank Chairman Alan Greenspan lowered the Federal Funds Rate to 1% in response to the equity bear markets, and the grinding decline in the equities market erased many of the gains from the nineties. Swensen’s Pioneering Portfolio Management seemed like it held the perfect solution. Alternatives would push back the efficient frontier, so managers could create “portfolios with higher returns for a given level of risk.” At that moment, it seemed that pension funds had no other option but alternative investments, and hedge funds were waiting with open arms.

The early 2000’s introduced a wave of allocations to hedge funds by pensions. Though not the first investments by pensions in hedge funds, allocations to hedge funds became far more widespread. CalPERS, for example, approved a revised investment plan in 1999 to include up to a 25% allocation of its public markets portfolio to hedge funds. CalPERS’ decision, if fully implemented at the time, would have entailed an investment of $11.25b into the nascent asset class. Remarking on the move, a spokesman said, “Hedge funds are not quite as risky as private equity funds, and we will steer clear of funds that use a lot of leverage to make bets on the market.” Hedge funds were still considered the frontier, but they were gaining broader and more enthusiastic acceptance.

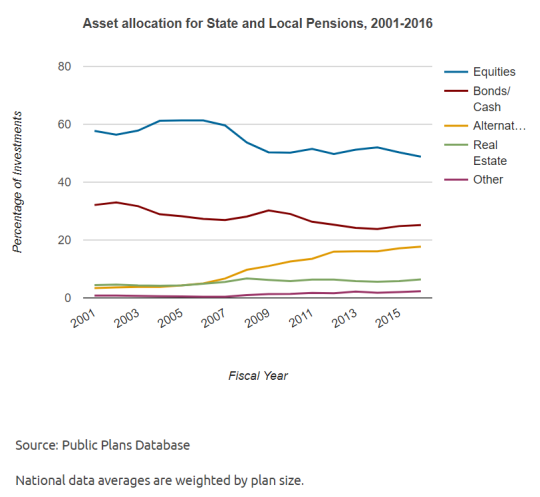

Public pension plans would grow their allocations to alternative investments dramatically over the coming years. Over the ten years from 2001 to 2011, pension plan allocations would increase from 3.5% to 13.5%. These would reach 17.7% in 2016, according to data from Public Plans Data, a joint effort between the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College (CRR), the Center for State and Local Government Excellence (SLGE), and the National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA). Much of the allocation to alternatives comprised allocations to hedge funds.

Hedge funds had their best year in a long time in 2017. The category was up 8.5%, according to HFR, and stock-pickers, in particular, did well. They were on average up 13.2%, and some outpaced the strong performance of the S&P 500. Outliers, such as Whale Rock Capital and Light Street Capital, were each up 36.2% and 38.6%, respectively. But investors have reservations. They pulled $70b out of the hedge funds in 2016 and barely changed their allocation in 2017. According to Don Steinbrugge, CEO of Agecroft Partners, in investment consultant, “The hedge fund industry remains oversaturated…We believe approximately 90 per cent of all hedge funds do not justify their fees … Some large managers are simply too large to maintain an edge.” They may have been up, but the S&P was up 19%, and the S&P doesn’t charge two-and-twenty.

The macro demands on pensions set the stage for a disruptive change in portfolio allocations, and David Swensen provided the playbook for allocating to hedge funds and alternatives, but today, it’s starting to feel like they may be too large to maintain an investment edge and too expensive to leave any returns over for their investors. That may be why hedge funds feel less like a disruptive force than an ordinary, if over-sold, component of a portfolio.