Hands Across New Jersey

How a 1990 tax rebellion rewired the state’s finances and set the stage for decades of rising property taxes

The phone rang.

"Hi, my name is John Budzash,” the caller said, “and I want to talk to John and Ken about organizing a protest where we all link hands across the state to protest all of these Florio tax hikes."

The year was 1990. Budzash was a 39-year-old Howell Township postal worker, and John and Ken were DJs for New Jersey’s FM 101.5 in Trenton where the slogan was, “Now you're in charge of the government,” and the conversation tilted against taxes, tolls and government overreach.

John and Ken put Budzash on the air, and he shared his idea with the rest of New Jersey. Another call followed: “Hi, my name is Pat Ralston, and I agree with that guy John about a protest across New Jersey, and I want to help him organize it." Ralston was a forty-six year old grandmother from Belmar, NJ who was fond of telling people, ''I tell people that my name is Pat and I'm mad as hell and I'm going to do something about it.''

Nine days later, with a little help from John, Ken, Pat and the drumbeat of FM 101.5, Budzash had his rally.

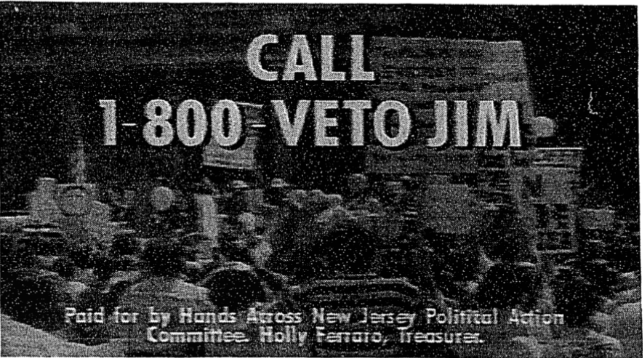

Demonstrators blocked forty miles of Interstate 195 and overran the streets of Trenton. The police closed West State Street to accommodate more than 6,000 protestors (NYT). Angered by Florio’s intention to extend the sales tax to paper products, protesters draped the grounds with toilet paper. To Budzash it was no different than the British tax on tea that set off the American Revolution: “When they taxed the toilet paper, they did the same thing here.” A proto tea party movement was born: Hands Across New Jersey.

The 1990 tax revolt may not have succeeded, but it didn’t disappear. It would return as a structural fiscal crisis that still defines New Jersey today. Christine Todd Whitman campaigned in 1993 on a promise to roll back the so-called Florio tax increases. She won, and the subsequent cuts, justified as tax relief, undermined state pensions and diverted state funding from municipalities. Municipalities were forced to raise funds in the only way they could – property taxes. Politically, it was a stroke of genius. Shifting the burden to local governments, ensured municipalities would take the blame for taxes, not Whitman.

When Jim Florio won the Governor’s race in 1989, his predecessor, Governor Thomas Kean, claimed Florio would inherit a budget surplus. As the year came to a close the surplus had rapidly shifted to a deficit. The economy had turned toward recession. The profligate eighties had left New Jersey with a budget that had increased 14% a year. In the latter half of the eighties, property taxes had been rising 12-13% a year, just to keep up. When Florio became governor, the government was running out of cash, and the people of New Jersey had had enough.

The crisis was not confined to New Jersey. Employment growth in the US had been slowing through 1989, and manufacturing was hit particularly hard: “sizable manufacturing job losses occurred in each of the last four months of 1989.” Though inflation had subsided somewhat by the second half of the year, prices were still up 4.6% year over year in December, and wage pressures were even higher – 4.8%. Meanwhile, unit labor costs had increased 5%, compared to a 3% increase the prior year. The difference indicated a mix of declining productivity and higher compensation costs. Starting in June 1990, the unemployment rate began its steady march upward, from 5.2% to 7.8% in June of 1992.

Many chose to go on TV and address their constituents with the seriousness of the situation. On August 15, 1990, Governor Florio delivered a 25-minute address live on WWOR-TV that would be rebroadcast throughout the state. He asked voters to do the responsible thing and balance the budget through a combination of tax increases and budget cuts. Florio said, ''Nobody likes taxes…'The question is what are you going to do about a $3 billion deficit? I have decided to face up to it and give the people of our state honest answers.'' There was one problem. He had guaranteed throughout his campaign that he would not raise taxes. Taxpayers said he had lied.

Governor Florio announced a $2.8b tax hike – the largest state-initiated tax increase in the history of the US. He promised cuts throughout the government. He would eliminate fleets of government cars. He would stop printing glossy leaflets. He fired people en masse – more than 1,500 state employees. He just wanted to have the 10% of voters who made more than $100k at the time pay a little more in taxes. It would only affect 17% of taxpayers. Most would see no change, and may would experience tax relief. Most of the burden will fall on the ten percent of families with incomes of more than $100,000. The money would support schools and municipal services, help end the cycle of rapidly escalating property taxes, and fill the hole left by the prior administration.

The plan worked and put New Jersey on a more sustainable fiscal path. Property taxes would rise only 1.4% in 1991. Regardless of how targeted or fair or responsible the tax increase was, however, it was all that anyone would talk about.

Christine Todd Whitman entered the 1993 campaign for governor as the republican, anti-tax candidate. She had nearly won an upset against Senator Bill Bradley in 1991 on the heels of Hands Across New Jersey. Budzash, having quit Hands Across New Jersey because it had been taken over by Republicans, attempted and failed to get on the Democratic ballot. Complaining that Whitman didn’t offer any substance, Budzash would endorse Florio saying, "Hey, a lot of people are just like me…They can't believe it, but they're voting for Florio." FM 101.5 program director Perry Michael Simon would say, "The mood out there isn't as much kindly disposed to Florio as much as it's dispirited about the alternative."

Christine Todd Whitman beat Governor Florio by twenty-six thousand votes. She had campaigned on rolling back Governor Florio’s $2.8b tax increase through a 30% tax cut. Her tax cut, pushed through in 1994, made her a political star. To pay for the tax cuts, she made two policy decisions. First, she lowered state contributions to the pension plans. Second, she diverted state tax revenues from funding from municipal services. Municipalities relied on property taxes, but they were also funded by a system that directed state taxes to municipal and school budgets. The only problem was, if she did, how would municipalities continue to fund services like police, fire, education?

Enter a pair of economists who leaned on the so-called flypaper effect to provide Whitman the expert-led support for cutting funding to municipalities. Economists Timothy J. Goodspeed and Peter D. Salins claimed that if state funding to municipalities went up by a dollar, they would spend the money, but if state funding to municipalities went down, “for every dollar the average New Jerseyan's income taxes are cut, he or she will have to pay only an extra 22 cents in local taxes.” If the plan worked, it would mean more money in each New Jersey resident’s pocket – on average. They published a triumphant New York Times editorial on March 16, 1996, New Jersey's Tax Cuts Have Worked and pushed for every state to follow suit.

Salins and Goodspeed didn’t think that property taxes wouldn’t go up. They just believed the flypaper effect would limit their rise, and any property tax increases would be more than offset by the income taxes returned to New Jersey residents in the form of the income tax cut. Their prediction, however, applied to the average welfare of New Jersey residents, not all New Jersey residents. Many found themselves in the position of the man on the street.

Lower income taxes would return more income to New Jersey residents, but it did so based on income levels. Those with higher income levels may find themselves feeling wealthier, despite a property tax increase, but those at lower income levels may find themselves in the position of the man on the street in the PBS segment. The property tax increase triggered by the tax cuts more than offset the effect of lower income taxes. Because Florio’s tax increases had targeted the ten percent of households with higher incomes, the corresponding Whitman tax cuts skewed towards those with higher incomes. Therefore, ninety percent of households felt little income tax relief while being asked to pay all the more in property taxes.

Property taxes, meanwhile, began increasing – dramatically. The Whitman tax cut and corresponding freeze of state funding to municipalities increased property taxes 5% in 1995. Democratic lawmakers warned, "Property taxpayers beware.” In 1997, they increased 3% on average, and in two dozen municipalities, they increased by double digits. Bernards Township in Somerset County was forced to raise property tax bills an estimated 17% to accommodate new families that had moved to town. Moreover, those were only estimates at the time. The actual numbers wouldn’t be released until after the November 4th election (NYT). Her Democratic opponent, Jim McGreevey would say, “The Governor said earlier in her term that property taxes were not her problem, and she has proven it by pushing them upwards by $1.9 billion in only four years.”

The ninety percent of households found themselves squeezed between meager income tax relief and escalating property tax bills, and and the cycle would soon exhaust the ten percent.

State pension liabilities, meanwhile, increased the strain on New Jersey’s budget. Governor Whitman had assured voters in 1994 that the pension system was overfunded and proceeded to reduce the state’s contribution schedule established by Governor Florio to fully fund the pension liabilities. Reducing the state’s contribution to its seven pension funds had helped make the income tax cuts possible. The “savings” helped balance the budget, but the decision converted what had been an $800m unfunded liability into a one that stood at $4.2b in 1997 (NYT).

The wealth effect of the late nineties equity bubble, however, seemed capable of papering over the problems. Governor Whitman would take the highly unusual step of using leverage to invest in equities, so the people of New Jersey could benefit from the rising equity market. New Jersey sold $2.75 billion of bonds paying 7.6% interest in 1997. The proceeds went directly into an investment program in the state pension fund named the Pension Security Plan. She assured the people of New Jersey that they would save $45 billion in the process. The first year yielded handsome returns, but the so-called Pension Security Plan did not even cover the cost of capital. It earned less than 6% annually through 2009.

Governor Whitman would continue to raise the prospect of tax cuts and rebates for citizens, but many had lost patience with her policies. Responding in 1998 as a man on the street in the New York Times, one resident of Iselin put it bluntly (NYT), “If she were interested in providing tax relief, why not give back the revenues she stole from municipalities in her 30 percent income tax reduction?” Republican State Senator from Middletown Township and a member of the Senate budget committee Joseph M. Kyrillos Jr. said, in a moment of candor, “There is really no easy answer to this.... With property taxes, we may not be able to afford all the government that we now have.” Indeed, the state government envisioned and organized by Governor Whitman was no government at all.

In the end, John Budzash got what he wanted. He had called thousands to the streets of Trenton in 1990 to fight Governor Florio’s tax increase. Christine Todd Whitman converted that support into a successful campaign for governor and made good on the promise of Hands Across New Jersey. But all she really did was shift the burden from the statehouse to the town halls across the 566 municipalities in New Jersey. As the state withdrew, towns were forced to balance budgets on property taxes. Between 2000 and 2008, property taxes jumped more than 50%. Extend that period to 2010, and the total increase is 60%.

Thirty years later, New Jersey is still paying for its tax revolt — still overtaxed, still underserved, still angry at a government that long ago gave the people exactly what they asked for.